June

18

June

18

Tags

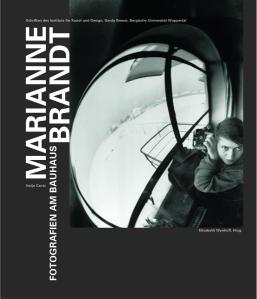

Modernism Uncut: Marianne Brandt’s Photomontages

On the 18th of June 1983, German artist Marianne Brandt died in Kirchberg, Saxony at the age of 89. She was a complex multi-media artist and designer nowadays best remembered for creating metallic household objects such as lamps, ashtrays and teapots which are at the forefront of modern industrial design. Starting with 1926, Brandt also produced a body of photomontage work, little known until the 1970s after she had abandoned the Bauhaus style and was living in Communist East Germany. In these multifaceted works, Brandt directed her analytical attention to prevalent issues in contemporary society and politics following WWI. Inspired by the multitude of visual material made available by the Weimar Republic’s emerging illustrated press, Brandt started cutting and pasting images and printed material into witty photomontages.

On the 18th of June 1983, German artist Marianne Brandt died in Kirchberg, Saxony at the age of 89. She was a complex multi-media artist and designer nowadays best remembered for creating metallic household objects such as lamps, ashtrays and teapots which are at the forefront of modern industrial design. Starting with 1926, Brandt also produced a body of photomontage work, little known until the 1970s after she had abandoned the Bauhaus style and was living in Communist East Germany. In these multifaceted works, Brandt directed her analytical attention to prevalent issues in contemporary society and politics following WWI. Inspired by the multitude of visual material made available by the Weimar Republic’s emerging illustrated press, Brandt started cutting and pasting images and printed material into witty photomontages.

The first ever overview and collection of these works can be found in Elizabeth Otto’s catalogue to the 2005-6 exhibition of the same name Tempo, Tempo! The Bauhaus Photomontages of Marianne Brandt. Her “bilingual book features 45 meticulously constructed and multilayered montages that capture manifold dimensions of the period of economic and social flux between the two world wars. The 45 short essays that accompany these photomontages are detailed, in formative analyses that offer readers a deeper understanding of Brandt’s aesthetic influences and socio-political orientation. Using photographs from the popular Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung as well as personal snapshots, Brandt created humorous, often critical commentary about the world around her. Many of the montages, such as Helfen Sie Mit! (Die Frauenbewegte) and Miss Lola, are celebrations of the New Woman, the emancipated, educated woman of the 1920s, of which Brandt herself was emblematic.” (Sydney Norton in German Studies Review, Vol. 30, No. 3, Oct., 2007). By challenging pictorial conventions, Brandt imagined new roles for women. In the interwar period, women benefitted from new freedoms in work, fashion and sexuality, yet had to face old-fashioned prejudices all the same. One of Brandt’s photomontages entitled With all Ten Fingers (c.1930) has two figures placed in a large field of white: a kneeling woman with uplifted arms at the lower left, and a businessman at the top right. Connecting lines between them make it appear as if the man is manipulating the woman like a marionette. Otto reads this photomontage as a way for Brandt to “problematize the predicament of women in the unstable conditions of the last years of the Weimar Republic”. It’s title “with all ten fingers” is a sarcastic hint at the fact that, a fully capable woman is rendered helpless, pointing to the unequal power balance between urban professional men and women in the interbellic period.

Other pieces in this series tackle issues such as war propaganda in the media (Flugzeug, Soldaten und Soldaten Friedhof), as well as international celebrity and modern architecture, with images from Paris, Berlin, New York, and Hollywood. Melissa Johnson claimed that by juxtaposing popular icons of mass entertainment, such as Marlene Dietrich, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and Josephine Baker, with disturbing scenes from WWI and European colonial life, Brandt tried to highlight some of the worrying aspects of the Western modern world.

Other pieces in this series tackle issues such as war propaganda in the media (Flugzeug, Soldaten und Soldaten Friedhof), as well as international celebrity and modern architecture, with images from Paris, Berlin, New York, and Hollywood. Melissa Johnson claimed that by juxtaposing popular icons of mass entertainment, such as Marlene Dietrich, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and Josephine Baker, with disturbing scenes from WWI and European colonial life, Brandt tried to highlight some of the worrying aspects of the Western modern world.

The most important contribution of Brandt’s photomontages though was her questioning of the limits of modernism. This was the end result of a combination of influences. Otto shows that Brandt’s photomontages were influenced by Siegfried Kracauer’s critique of Weimar culture in relation to female mobility and flanerie (Fr. for aimless idle behaviour), Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s theories of the formal properties of photographs and his interest in Alois Riegl’s theories of the haptic and optic, as well as the writing of Walter Benjamin. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin debated that the “breaks and blank spaces” in avant-garde photomontage could be seen as abstract spaces which cannot be interpreted symbolically; they simply stood for themselves, they were the necessary voids between bits of representational, figurative or concrete photo images, which took these unusual works to a different conceptual level.

“Photomontage, in general, demands careful looking, and Brandt’s are no exception. Visually striking, they at first bring to mind Walter Benjamin’s observations on Dadaist photomontage. Benjamin wrote that the Dadaists valued their work for “its uselessness for contemplative immersion” and the “destruction of the aura of their creations.” In both, he noted, the Dadaists anticipated the shock effects of film. Dadaist photomontage, like film, “became an instrument of ballistics. It hit the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality.” Though Brandt was not a Dadaist, her relatively large and highly graphic photomontages provide this initial visual and tactile jolt. Our gaze does not settle easily in just one place, rather, as Benjamin quotes Georges Duhamel, we “can no longer think what [we] want to think. [Our] thoughts have been replaced by moving images.” Only with attentive examination do the complex combinations of images, the layers, cut edges, different media sources, become apparent. This is somewhat paradoxical, of course, because the point of much  1920s photomontage, Brandt’s included, was to reflect the chaotic and ephemeral nature of modernity. Brandt’s photomontages both reference and reject Dadaist practices at the same time. They seem simultaneously to invoke, yet halt, the perpetual movement of 1920s modernity to provide a means of analysis. Upon the image-filled surface of her photomontages Brandt often provided a central figure, or sometimes several figures, gazing out at the spectator, offering a locus of contemplation and entry into the photomontage.” (Melissa A. Johnson in Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1, Spring – Summer, 2008). Photomontage has lately been studied more carefully as a means of modernist expression and Marianne Brandt can naturally be considered one of the pioneers in this unprecedented medium. Some of these works can be seen here.

1920s photomontage, Brandt’s included, was to reflect the chaotic and ephemeral nature of modernity. Brandt’s photomontages both reference and reject Dadaist practices at the same time. They seem simultaneously to invoke, yet halt, the perpetual movement of 1920s modernity to provide a means of analysis. Upon the image-filled surface of her photomontages Brandt often provided a central figure, or sometimes several figures, gazing out at the spectator, offering a locus of contemplation and entry into the photomontage.” (Melissa A. Johnson in Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1, Spring – Summer, 2008). Photomontage has lately been studied more carefully as a means of modernist expression and Marianne Brandt can naturally be considered one of the pioneers in this unprecedented medium. Some of these works can be seen here.

Interesting Read!

LikeLike

Pingback: In Author Amber Brandt's Debut Novel, a Young Woman Seeks Her Destiny in a Magical World | News Canada Binary

I love Brandt! And I love you guys for remembering her!

LikeLike