June

02

June

02

Tags

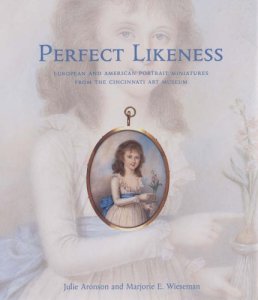

The Portrait Miniature: Art-Object-Memory

On the 2nd of June 1804, Danish 18th century Court miniaturist and Royal Danish Academician Cornelius Høyer died in København, Denmark. The works Høyer executed for the Danish and other European courts were diminutive in size, often 40 mm × 30 mm or approximately 1-1.5 inches, oval or round in shape. Among his best known pieces is a portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven from 1802, a particularly handsome rendering and favourite of the composer himself.

On the 2nd of June 1804, Danish 18th century Court miniaturist and Royal Danish Academician Cornelius Høyer died in København, Denmark. The works Høyer executed for the Danish and other European courts were diminutive in size, often 40 mm × 30 mm or approximately 1-1.5 inches, oval or round in shape. Among his best known pieces is a portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven from 1802, a particularly handsome rendering and favourite of the composer himself.

The beginnings of miniature painting go back as far as the 15th century. Miniatures were first painted to decorate and illustrate hand-written books. Indeed, the word ‘miniature’ comes from the Latin word ‘miniare’. This means ‘to colour with red lead’, a practice that was used for the capital letters. From the 1460s hand-written books had to compete with printed books. At the same time, however, wealthy patrons demanded a wider range of luxury goods. Miniaturists such as the Flemish Simon Bening continued to illustrate expensive books, but also offered patrons independent miniatures. Some were for private worship, others simply desirable objects. Portrait miniatures first appeared in the 1520s, at the French and English courts. Like medals, they were portable, but they also had realistic colour. The earliest examples were painted by two Netherlandish miniaturists, Jean Clouet working in France and Lucas Horenbout in England. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

“Portraits in miniature occupy an uncertain place in art historical studies. In public galleries they are exhibited in glass cases covered by cloth to protect them from daylight, and visitors often walk straight past them. They are seen as a branch of portraiture, but a minor one; their dimensions encompass a range from the truly diminutive to a painting too large to put in a pocket but small enough to be passed around a dinner table. Their size and the fact that they are often executed in watercolour relegate them to the margins of a genre associated widely with grand public images or psycho-logically penetrating evocations. (…) Historians of jewellery, on the other hand, view the portrait miniature as incidental; it is the surviving jewelled case or frame that is the focus of their interest. Miniatures and the cases or frames in which they were originally mounted, moreover, are frequently separated  and the miniatures reframed in accordance with a schema that stresses their presence as images on flat surfaces rather than as part of a three-dimensional artifact.” (Marcia Pointon, ‘ “Surrounded with Brilliants”: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 83, No. 1, Mar., 2001).

and the miniatures reframed in accordance with a schema that stresses their presence as images on flat surfaces rather than as part of a three-dimensional artifact.” (Marcia Pointon, ‘ “Surrounded with Brilliants”: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 83, No. 1, Mar., 2001).

Due to portrait miniatures providing very detailed depictions of the sitter, their likeness to the subject portrayed, they remained highly popular until the development of daguerreotypes and photography in the mid-19th century. They were a very effective early historical form of image reproduction, especially useful in introducing people to each other over distances, such as future spouses in arranged marriages, soldiers, sailors and their families carrying miniatures of loved ones who were away from them for prolonged periods of time. Or courtiers wearing miniatures of their king or queen as a sign of loyalty.

The medium in which these tiny works were produced varied between gouache, watercolour, or enamel. The first miniaturists used watercolour to paint on stretched vellum. During the second half of the 17th century, vitreous enamel painted on copper started being used, especially in France. In the 18th century, miniatures were painted with watercolour on ivory, which had now become more affordable. Artists experimented with ways to make it easier to paint on ivory such as, roughening the ivory, degreasing it and making the watercolour paint stickier. The first British artist to paint on ivory was Bernard Lens, in about 1707. At the same time that ivory replaced vellum, miniatures tended to become smaller, probably because of the difficulty of using watercolour on ivory. Another reason might have been the fashion for the diminutive enamel portraits. Portrait miniatures often served as personal mementos or as jewellery or snuff box covers.

Marcia Pointon, the author of Portrayal: and the Search for Identity (2012) writes about an even more intimate form of portrait miniature hailing from the nineteenth-century “in which only the eye was depicted. These miniatures were often framed and mounted in lockets and thus became tokens of love or friendship in which only th e owner had the key to the identity of the sitter.’ Miniatures were portraits which were not only images but also objects, things to be held, handled, moved about, hidden, treasured or collected. Pointon calls these ‘portrait-objects’ and shows that exhibition facilities throughout history have not given them justice, which in turn caused them to be neglected by art historians. “The gazing game for which the portrait-object is the prerequisite, a game that links private and public spaces, works to define individual subjectivity in ways that are socially infectious. In so doing it subverts the hegemony of full-scale portraiture. The dominant genre of the publicly exhibited large-scale image reasserts its claim to authority and negates the materiality of the portrait-object by incorporating the miniature as mise-en-abyme, thus producing a potentially endless process of deferral.” (Marcia Pointon)

e owner had the key to the identity of the sitter.’ Miniatures were portraits which were not only images but also objects, things to be held, handled, moved about, hidden, treasured or collected. Pointon calls these ‘portrait-objects’ and shows that exhibition facilities throughout history have not given them justice, which in turn caused them to be neglected by art historians. “The gazing game for which the portrait-object is the prerequisite, a game that links private and public spaces, works to define individual subjectivity in ways that are socially infectious. In so doing it subverts the hegemony of full-scale portraiture. The dominant genre of the publicly exhibited large-scale image reasserts its claim to authority and negates the materiality of the portrait-object by incorporating the miniature as mise-en-abyme, thus producing a potentially endless process of deferral.” (Marcia Pointon)

Looks like these artist were not “small time” after all.

LikeLike

Yes, Carl, it does seem like they were not only difficult to make but also very popular!

LikeLike

Alright, I read this and then read the last bit in bold, by Marcia Pointon (I think), and then I read it again, the last bit that is, and had no idea what mise-en-abyme was or meant, all the while attempting to pronounce it (most likely incorrectly) and in so doing coming to the conclusion (possibly erroneously) that it was an unpleasant word(s), until finally, realizing I should find out what it actually means, so as not to toss and turn needlessly when attempting to sleep later, did, and now plan to squeeze it into conversations whenever possible.

Thank you

The President and Founder

LikeLike

Yes, quite an intricate quote. What the author means is that miniature portaits stay in the shadow of full-scale portraiture, at least from an art historical point of view. She basically just uses the word here as a metaphor for them being forgotten (placed in the abyss), while playing on the idea of the mise-en-abyme as an actual painting technique, in which an image is being repeated generally by mirroring with a smaller image of itself, bit like in Van Eyck’s Arnolfinis or Velazquez’s Meninas. But I am sure you know all this already! Welcome and enjoy our site!

LikeLike

English Renaissance miniatures seem to fare better in art history annals. You may be surprised that a well lived Elizabethan image, reproduced in art history texts alongside canvas and panel paintings is actually a miniature. In terms of my own interest both in miniatures and jewellery history, I find it annoying that clear images of the miniature in its mount are not reproduced.

A very enjoyable post!

LikeLike

Thank you, crafty theatre! Your input is always appreciated.

LikeLike

Today i spent 300 bucks for platinium roulette system , i hope that

i will make my first money online

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Windows into History (Reblogging and Links) and commented:

Suggested reading – a very useful blog for anyone interested in the history of art. Reblogged on Windows into History.

LikeLike