May

06

May

06

Tags

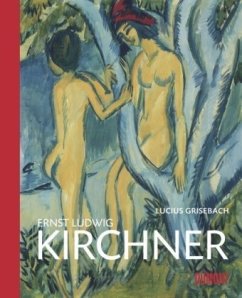

Depravation in the Art of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

On the 6th of May 1880, Expressionist artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born in Aschaffenburg, Germany. One of the leading names in the Die Brücke movement, his art was deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and destroyed in great numbers. The artist ended his life by gunshot at the age of 58 at his house in exile in Switzerland. He was a complex, sensitive and troubled character who suffered a mental breakdown during war service, and later substance and alcohol addiction, depressive episodes, and hypochondria.

On the 6th of May 1880, Expressionist artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born in Aschaffenburg, Germany. One of the leading names in the Die Brücke movement, his art was deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and destroyed in great numbers. The artist ended his life by gunshot at the age of 58 at his house in exile in Switzerland. He was a complex, sensitive and troubled character who suffered a mental breakdown during war service, and later substance and alcohol addiction, depressive episodes, and hypochondria.

From the start of his career as an artist, Kirchner was drawn to the unconventional and the controversial: his studio became a venue in which social conventions were obliterated to allow casual love-making and frequent nudity. There were group life-drawing sessions with models from the painter’s social circle, amongst which, girls as young as 15, rather than professional models. In Kirchner’s art, there was a strong emphasis on intuition and spontaneity, his models being asked to adopt 15 minute poses instead of sitting for lengthy studies. During 1914-15, Kirchner painted the famous “Großstadtbilder” (metropole pictures) showing the streets of Berlin, focusing on the central characters of street walkers. The street scenes from 1913-15, such as his crayon and tempera drawing Cocotte in Red, explored the subjects of luxury and immorality in art linked with the realms of advertising, and fashion. Sherwin Simmons pointed out that Kirchner’s preference for these subjects also stemmed from personal motivations, particularly his fear of having contracted syphilis, the ailment of the debauched bohemia:

“During 1915-16 his portrayal of sexuality had broadened to include same sex and multiple-partner relationships, masturbation, and various forms of fetishism. Sexual boundaries loosened at the same moment that he began to fear that a sexual disease might endanger the faculties necessary for his art. It was a danger that he shared with the women closest to him, for recently published information indicates that Erna Schilling had the disease at the time she met Kirchner, and Gerda Schilling died of the disease in 1923 while living in the Prussian State Mental Hospital. Looking back at the Strassenbilder from his new context, Kirchner interpreted the streetwalkers allegorically, identifying himself with the degradation and marginality he saw in them.” (Sherwin Simmons, ‘Ernst Kirchner’s Streetwalkers: Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 1, Mar., 2000).

“During 1915-16 his portrayal of sexuality had broadened to include same sex and multiple-partner relationships, masturbation, and various forms of fetishism. Sexual boundaries loosened at the same moment that he began to fear that a sexual disease might endanger the faculties necessary for his art. It was a danger that he shared with the women closest to him, for recently published information indicates that Erna Schilling had the disease at the time she met Kirchner, and Gerda Schilling died of the disease in 1923 while living in the Prussian State Mental Hospital. Looking back at the Strassenbilder from his new context, Kirchner interpreted the streetwalkers allegorically, identifying himself with the degradation and marginality he saw in them.” (Sherwin Simmons, ‘Ernst Kirchner’s Streetwalkers: Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 1, Mar., 2000).

So, there was a sense in which Kirchner may have interpreted the street walkers symbolically as his own outsider status as artist and producer of a form of novel expressive art, shunned in his native Germany for both political, economic and aesthetic reasons: “the prostitute body has become “the feminine as allegory of modernity.” Spleen and melancholy surface […]  as the market forced recognition of his precarious position within an art world being transformed by commerce. Kirchner was assailed by anxiety as a given identity was loosened, feminized in cultural and psychic terms, and forced into prostitution.” (Simmons). At the same time, one must not overlook the fact that Kirchner’s foremost intention was not that of documenting a social reality, but an aesthetic universe, full of sensuous and sensory attractions. This is evident in the artist’s own words, marking his discovery of what was to become one of his favourite subjects, the ‘coquette’ or ‘cocotte’, depending on his disposition and context: “In 1929 I saw a blond woman in Berlin walking wonderfully with long legs, who I cannot get out of my mind, built so slender, exquisite, and totally sensual, such as I had never seen before.” (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Cocotte in Red, 1914. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung). Considering Kirchner’s eye for beauty, it is fair to say that he saw his streetwalkers as aesthetic objects, rather than studies in morality. This was an artist who saw aesthetic potential in the fleeting moments of life and the risqué protagonists of a fascinating alternative underworld seemed the most unlikely sources to provide just that.

as the market forced recognition of his precarious position within an art world being transformed by commerce. Kirchner was assailed by anxiety as a given identity was loosened, feminized in cultural and psychic terms, and forced into prostitution.” (Simmons). At the same time, one must not overlook the fact that Kirchner’s foremost intention was not that of documenting a social reality, but an aesthetic universe, full of sensuous and sensory attractions. This is evident in the artist’s own words, marking his discovery of what was to become one of his favourite subjects, the ‘coquette’ or ‘cocotte’, depending on his disposition and context: “In 1929 I saw a blond woman in Berlin walking wonderfully with long legs, who I cannot get out of my mind, built so slender, exquisite, and totally sensual, such as I had never seen before.” (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Cocotte in Red, 1914. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung). Considering Kirchner’s eye for beauty, it is fair to say that he saw his streetwalkers as aesthetic objects, rather than studies in morality. This was an artist who saw aesthetic potential in the fleeting moments of life and the risqué protagonists of a fascinating alternative underworld seemed the most unlikely sources to provide just that.

Another artist to join Munch and others in an exploration of alienation!

LikeLike

Another artist to join Munch and others in an exploration of alienation!

LikeLike

Another artist to join Munch and others in an exploration of alienation!

LikeLike

I dont know why its copied 3 times!??

LikeLike

Great post! Especially as “degenerated” art is the subject of a few current exhibitions. Thanks for bringing this to our attention!

LikeLike

do you call sex depravation …. i mean it is strange … sex is sex depravation is not sex

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Manolis.

LikeLike