August

30

August

30

Tags

The Tragedies of Mary Shelley

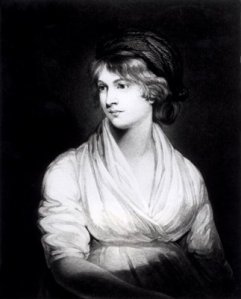

On the 30th of August 1797, English novelist Mary (Wollstonecraft) Shelley was born in London. She was the wife and muse of Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley, daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and of philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, she was most famous for her Gothic novel Frankenstein (1818). Much of Mary Godwin’s personal life was fraught with misfortune and grief. Almost as soon as she had given literary birth to her hideous creature Frankenstein, her world began to disintegrate.

On the 30th of August 1797, English novelist Mary (Wollstonecraft) Shelley was born in London. She was the wife and muse of Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley, daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and of philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, she was most famous for her Gothic novel Frankenstein (1818). Much of Mary Godwin’s personal life was fraught with misfortune and grief. Almost as soon as she had given literary birth to her hideous creature Frankenstein, her world began to disintegrate.

Tragedy was present very early on in Mary’s life when she lost her mother at only eleven days of age. After her publication of Frankenstein, however, something akin to a curse seems to have descended on her circles. In 1816, Mary’s troubled half-sister Fanny Imlay Godwin checked herself in to a hotel in Wales and committed suicide with an overdose of laudanum. Two months later, her lover Percy Shelley’s wife Harriet threw herself into a river and committed suicide as well. This latter tragedy allowed Percy and Mary to make their relationship legal. On the 30th of December 1816, Percy Shelley and a pregnant Mary Godwin married in London. Because of his outspoken beliefs in free love, Shelley was not granted legal custody of his children with Harriet Westbrook. Throughout Percy Shelley’s life, his wife Mary was usually overshadowed by her famous husband and her subsequent written work was mention only as produced by “The Author of Frankenstein.”

Italy proved to be the site of Shelley’s greatest heartaches. In September, six months after they arrived, her firstborn Clara Everina contracted dysentery and died. In June 1819, her three-year-old son William died of malaria. Now Mary and Shelley had no living children, though she was pregnant with their fourth. She became deeply depressed. Their son, Percy Florence, was born 12 November  1819. He was the only one of the couple’s four children to outlive his parents. A fifth child miscarried later. On 8 July 1822, her husband Percy Shelley drowned in the Gulf of Spezia while sailing with a friend. The poet was a month shy of his thirtieth birthday. Mary Shelley was devastated. She had her husband’s body cremated. Shelley was now a widow with a small child and no way to support herself, so she returned to England. Life was no easier back in England. Many people refused to associate with Shelley because of her elopement with Percy a decade earlier. Shelley got to work instead on another science fiction novel entitled The Last Man. Just as Frankenstein gave birth to centuries of rip-offs and remakes, The Last Man introduced the popular device of mankind fighting for its very existence, as war and plague threaten to wipe it out. She was also able to circumvent Timothy Shelley’s prohibition on writing about his son by basing the fictional character of Adrian, Earl of Windsor on an idealized version of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her novel was a success, but Shelley was horribly lonely. “The last man! Yes I may well describe that solitary being’s feelings, feeling myself as the last relic of a beloved race, my companions extinct before me,” she wrote in her journal. “At the age of twenty-six I am in the condition of an aged person–all my old friends are gone … & my heart fails when I think by how few ties I hold to the world.” Writing saved her. Though she never again wrote anything as popular as Frankenstein, Shelley worked diligently on books and articles for the remainder of her life. By the late 1840s, Shelley was experiencing the first symptoms of the brain tumour that eventually took her life, trouble talking and paralysis. (Shmoop)

1819. He was the only one of the couple’s four children to outlive his parents. A fifth child miscarried later. On 8 July 1822, her husband Percy Shelley drowned in the Gulf of Spezia while sailing with a friend. The poet was a month shy of his thirtieth birthday. Mary Shelley was devastated. She had her husband’s body cremated. Shelley was now a widow with a small child and no way to support herself, so she returned to England. Life was no easier back in England. Many people refused to associate with Shelley because of her elopement with Percy a decade earlier. Shelley got to work instead on another science fiction novel entitled The Last Man. Just as Frankenstein gave birth to centuries of rip-offs and remakes, The Last Man introduced the popular device of mankind fighting for its very existence, as war and plague threaten to wipe it out. She was also able to circumvent Timothy Shelley’s prohibition on writing about his son by basing the fictional character of Adrian, Earl of Windsor on an idealized version of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her novel was a success, but Shelley was horribly lonely. “The last man! Yes I may well describe that solitary being’s feelings, feeling myself as the last relic of a beloved race, my companions extinct before me,” she wrote in her journal. “At the age of twenty-six I am in the condition of an aged person–all my old friends are gone … & my heart fails when I think by how few ties I hold to the world.” Writing saved her. Though she never again wrote anything as popular as Frankenstein, Shelley worked diligently on books and articles for the remainder of her life. By the late 1840s, Shelley was experiencing the first symptoms of the brain tumour that eventually took her life, trouble talking and paralysis. (Shmoop)

As Greg Kucich, contributor of the book Mary Shelley in Her Times “sifts through the huge body of Mary Shelley’s biographical essays, he is struck by her “tendency to find recurrent versions of her own traumatic experience of shattering loss and broken affection in the domestic histories of her subjects.” He goes on to  remark that her Lives “feature an array of grief-filled vignettes”, a comment that dovetails with eighteenth-century theatrical scholar Judith Pascoe’s emphasis on Mary Shelley as a mourner. (…) In quoting a passage from Mary Shelley’s journal written in the aftermath of Percy Shelley’s death, Pascoe comments that the passage opens up “a mode of being that, I think, is quite foreign to us now, one that involves living through and in tragedy rather than drawing oneself up and walking away and beyond”. To be aware that someone historically removed from us is “foreign” and thereby radically mysterious is surely the beginning of scholarly wisdom.” (Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, Mary Shelley in Her Times by Betty T. Bennett; Stuart Curran, in Modern Philology, Vol. 102, No. 3, February 2005). Tragedy seems to have become a way of life for Mary Godwin Shelley which fed through the entire body of her work and was poignantly present in pieces such as the compelling short story, The Mourner (1829), which you can read here.

remark that her Lives “feature an array of grief-filled vignettes”, a comment that dovetails with eighteenth-century theatrical scholar Judith Pascoe’s emphasis on Mary Shelley as a mourner. (…) In quoting a passage from Mary Shelley’s journal written in the aftermath of Percy Shelley’s death, Pascoe comments that the passage opens up “a mode of being that, I think, is quite foreign to us now, one that involves living through and in tragedy rather than drawing oneself up and walking away and beyond”. To be aware that someone historically removed from us is “foreign” and thereby radically mysterious is surely the beginning of scholarly wisdom.” (Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, Mary Shelley in Her Times by Betty T. Bennett; Stuart Curran, in Modern Philology, Vol. 102, No. 3, February 2005). Tragedy seems to have become a way of life for Mary Godwin Shelley which fed through the entire body of her work and was poignantly present in pieces such as the compelling short story, The Mourner (1829), which you can read here.

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog….. An Author Promotions Enterprise! and commented:

An interesting article from an interesting blog I follow 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a remarkable story of loss and literature. Thank you for it, and to you, Chris, for sharing it with us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Cynthia, hope you visit us soon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating to delve into the deep tragedies of a female writer from another time — wow and thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers, Mira! 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on mira prabhu and commented:

Fascinating to delve into the unbelievable tragedies that scarred the life of a famous female writer from another time — the author of no less than FRANKENSTEIN…wow and thank you Art Lake and the Story-Reading Ape…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Tragedies of Mary Shelley | Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog..... An Author Promotions Enterprise!

Thank you for a very interesting post. I didn’t know much about Mary Shelley before this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this! I just read Frankenstein and am fascinated by Mary Shelley. I am going to be teaching it this year so this is really useful for context. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on First Night Design.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The story of her half-sister is also tragic, she is buried in an unmarked grave in my home town of Swansea, hastily arranged because she was a suicide, with no-one to mourn at her funeral.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, I had no idea of the troubled life she had- that is incredibly tragic. What a remarkable woman to achieve what she did in life

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Tragedies of Mary Shelley — A R T L▼R K – gendering the british

Pingback: The Tragedies of Mary Shelley – Politics & chaos

So interesting and sad.

LikeLike

Incredibly interesting woman and life. A genuinely gifted person. Did you see the interpretation of her in the most recent Frankenstein done last year?

LikeLike

Fanny Imlay is buried in an unmarked grave in the graveyard of Saint Matthews church in Swansea, my home town. Godwin and Shelley allegedly bribed someone for her to be buried in consecrated ground, because she had committed suicide she shouldn’t have been, but no record of where the poor woman’s grave is.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Tragedies of Mary Shelley | A R T L▼R K | First Night Design

She is an author I’ve not thought much about, but ater reading this post I find her to have more substance than I expected Thank you.

LikeLike

Pingback: “What I’m Reading” — A Horror Recommendation from Matthew Carpenter | The Lovecraft eZine