September

14

September

14

Tags

Richard Gerstl, Self-Portraits of a Tortured Soul

On the 14th of September 1883, Austrian painter and draughtsman Richard Gerstl was born in Vienna; he is remembered for his insightful portraits and haunting self-portraits. He was born into a wealthy bourgeois family as the son of Emil Gerstl, a Jewish merchant, and Maria Pfeiffer, a Catholic woman who later converted to the faith. Against the wishes of his father, Gerstl became involved in the visual arts. In 1898 he attended the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, but became an anti-secessionist rebel, who did not manage to have his own exhibition during his lifetime as he clearly distanced himself from Secessionism. Today Gerstl is best known for his highly stylized heads executed in a raw form of expressionism using pastels, like Oskar Kokoschka.

On the 14th of September 1883, Austrian painter and draughtsman Richard Gerstl was born in Vienna; he is remembered for his insightful portraits and haunting self-portraits. He was born into a wealthy bourgeois family as the son of Emil Gerstl, a Jewish merchant, and Maria Pfeiffer, a Catholic woman who later converted to the faith. Against the wishes of his father, Gerstl became involved in the visual arts. In 1898 he attended the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, but became an anti-secessionist rebel, who did not manage to have his own exhibition during his lifetime as he clearly distanced himself from Secessionism. Today Gerstl is best known for his highly stylized heads executed in a raw form of expressionism using pastels, like Oskar Kokoschka.

Early on in his career, Gerstl was interested in philosophy and music and established friendships with composers such as Mahler, von Zemlinsky and Schoenberg. Whilst acting as an art tutor to the latter, Gerstl fell in love and had a relationship with his wife Mathilde; Schoenberg found the two in flagrante delicto in the summer of 1908. In desperation of losing Mathilde, Gerstl threatened the couple with suicide, but they decided to stay together for the sake of the children. Distraught by his unrequited love, his isolation from his associates, and his lack of artistic acceptance, Gerstl notoriously hung himself in front of a mirror, aged only 25, having also stabbed himself with a butcher’s knife. In a gesture of total self-annihilation, he burned his letters, documents and many of his paintings.

Academic Gemma Blackshaw finds that, in addition to his personal struggles, Gerstl’s artistic exploration of his tortured self could be attributed to his marginalised status as a young, anti-establishment Jewish artist in turn-of-the-century Vienna. “The centrality of Jews (… to Viennese fin-de-siecle culture, and the impact of an all-pervasive anti-Semitism on their self-definition, has been convincingly stressed in Vienna studies. (…) the innovations of Vienna’s key cultural producers of Jewish descent – Peter Altenberg, Sigmund Freud, Karl Kraus, Gustav Mahler, Arthur Schnitzler, Otto Weininger, Ludwig Wittgenstein (to give but a few examples) – have been rigorously investigated by scholars keen to place their work in active dialogue with the difference-intolerant nature of Vienna’s public sphere.(…) one of Vienna’s canonical modernist artists, Richard Gerstl – hailed by critics at the 1931 exhibition of his rediscovered work as the ‘Austrian Van Gogh’, an ‘adolescent phenomenon’ and ‘apostle of the co ming art’ – was Jewish by birth, and born into a family in which questions of faith were keenly felt.” (Gemma Blackshaw, ‘The Jewish Christ: Problems of Self-Presentation and Socio-Cultural Assimilation in Richard Gerstl’s Self-Portraiture’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2006).

ming art’ – was Jewish by birth, and born into a family in which questions of faith were keenly felt.” (Gemma Blackshaw, ‘The Jewish Christ: Problems of Self-Presentation and Socio-Cultural Assimilation in Richard Gerstl’s Self-Portraiture’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2006).

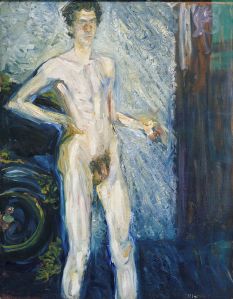

Scholars have been keen to point out this first identification of Gerstl with Christ, incorporating the self-portrait into wider discussions of the collective – and peculiarly Viennese – tendency of young, male artists to turn to Christ’s image and example during this 1905-1910 period. Gerstl’s self- portrait was brought seamlessly alongside those of his contemporaries, specifically Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele, in an attempt to underline the distinctiveness of their seemingly common project of self- representation. “The figure of the suffering, Christ-like artist developed by Gauguin and the Symbolists and embodied in the developing myth of Van Gogh perhaps found its most heightened expression in the self portraits of Egon Schiele and the Austrian Expressionists in the early years of the twentieth century. Artists such as Schiele, Gerstl and Kokoschka shared with Symbolists the desire to penetrate beyond external appearances, and a sense of the sacredness of the artist’s mission. (…) Richard Gersti’s extraordinary self portrait against a blue background makes explicit the Christ-like role of the artist as martyr, but perhaps even more powerfully suggests his role as redeemer. The symmetrically posed body recalls hieratic representations of Christ, as do his naked torso and the white cloth tied around his waist. Arms at his side, Gerstl confronts the viewer with a stare that combines immediacy and directness with a sense of remoteness.This sense of inaccessibility is heightened both by the otherworldly brightness of his torso and the glowing blue aura around his head and body. It is an image which recalls the Christ of the Passion, stripped to the waist, but more insistently suggests the Risen Or Transfigured Christ. The Jewish Gerstl painted this self portrait when he was in his early twenties; he was to paint many self portraits throughout his brief career, casting himself in a variety of roles, including what has been claimed as the first painted naked self portrait since Durer’s famous drawing of about 1506.” (Alexander Sturgis, Rebels and Martyrs: The Image of the Artist in the Nineteenth Century, National Gallery, 2006).

Scholar of modern Austrian art Gemma Blackshaw concludes that, “The identification with Christ was a means with which Gerstl could express his rejection and persecution by an intolerant society and culture, whilst simultaneously claiming his (undisputed) place within it. In other words, the turn to Christ was  a means of articulating socio-cultural exclusion and belonging. (…) Gerstl’s Durer-reliant representation of his perfected Artist-as-Christ body was not, however, nearly as marketable as the anguished and bloody gymnastics of Kokoschka and Schiele’s comparable self-portraits, so indebted to the city’s Roman Catholic visual culture. (…) By contrast, far from facilitating his undisputed position within Viennese culture, Gerstl’s cautious process of identifying with Christ only pointed to the ‘impossibility’ of his successful integration. We could interpret his suicide as a final attempt to embrace Christ’s example, in a manner befitting that of modernist myth-making.”(Gemma Blackshaw).

a means of articulating socio-cultural exclusion and belonging. (…) Gerstl’s Durer-reliant representation of his perfected Artist-as-Christ body was not, however, nearly as marketable as the anguished and bloody gymnastics of Kokoschka and Schiele’s comparable self-portraits, so indebted to the city’s Roman Catholic visual culture. (…) By contrast, far from facilitating his undisputed position within Viennese culture, Gerstl’s cautious process of identifying with Christ only pointed to the ‘impossibility’ of his successful integration. We could interpret his suicide as a final attempt to embrace Christ’s example, in a manner befitting that of modernist myth-making.”(Gemma Blackshaw).

Feature Image: Richard Gerstl, Semi-Nude Self-Portrait, 1904/05, oil on canvas, 159 × 109 cm (62.6 × 42.9 in), Leopold Museum, Vienna

Hi, Was pleased to see you feature Richard Gerstl, and my friend, Gemma Blackshaw’s essays, but as the accepted expert and biographer of the artist, I strongly recommend that you check out my website, richardgerstl.com, where you’ll find my doctoral thesis on the subject and accurate and evidence-based,versions of the circumstances surrounding all of Gerstl’s known works. You’re welcome to e-mail me at raymond.coffer@richardgerstl.com, if you need any more info. Thanks and best, Dr Raymond Coffer

LikeLike

Thank you, Dr Coffer. We will certainly make use of your expertise. Our mini articles don’t always allow enough time to do extensive research on each particular entry but we try our best to bring as much interesting information to our readers as we can. Welcome and hope you return to our blog soon!

LikeLike