May

18

May

18

Tags

Through the Female Lens: Gertrude Käsebier’s Indians

On the 18th of May 1852, leading American pictorialist photographer Gertrude Käsebier was born in Des Moines, Iowa. Artistically trained at the Pratt Institute, then in France and Germany, she started off as a magazine photo-illustrator, opening her own portrait studio on Fifth Avenue in New York at the end of the 19th century. Her work ‘Blessed art thou among women’ was among the photographs featured in the first issue of Alfred Stieglitz’ Camera Work in 1903. A divorced woman with children, she started her career late and against all odds attained great success and fame for a woman of her position and era, becoming a role-model for others to follow, such as Imogen Cunningham. She is known for being one of the first female artists to advise women to train professionally in the “unworked field of modern photography” to earn an independent living.

On the 18th of May 1852, leading American pictorialist photographer Gertrude Käsebier was born in Des Moines, Iowa. Artistically trained at the Pratt Institute, then in France and Germany, she started off as a magazine photo-illustrator, opening her own portrait studio on Fifth Avenue in New York at the end of the 19th century. Her work ‘Blessed art thou among women’ was among the photographs featured in the first issue of Alfred Stieglitz’ Camera Work in 1903. A divorced woman with children, she started her career late and against all odds attained great success and fame for a woman of her position and era, becoming a role-model for others to follow, such as Imogen Cunningham. She is known for being one of the first female artists to advise women to train professionally in the “unworked field of modern photography” to earn an independent living.

In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio towards Madison Square Garden. She promptly sent a letter to Bill Cody requesting permission to photograph the Sioux travelling with his show. These were circus-type show men reenacting often battle scenes from the Wild West, many of which their elder had historically and literally taken part in. Käsebier claimed that she was spurred by nostalgia for the Indian friends she had made during four childhood years spent near the boom-town of Golden, Colorado. On April 10, 1898, the New York Times included the following notice on its “Woman’s Page”: “There was a studio tea up town one day last week which probably exceeded in originality anything in the nature of an entertainment of that kind ever given. In the first place, the men outnumbered the women three to one, and their attire was more gorgeous than anything that was ever seen in the most startling ball gown, diamonds, perhaps, being excepted. The tea was given in the morning, which was also unique, but quite in keeping with the other features of the affair…. The studio was that of Mrs. Gertrude Käsebier and the gentlemen present were, among others, Mr. High Heron, Mr. Has No Horses, Mr. Sammy Lone Bear, Mr. Shooting Pieces, Mr. Iron Tail, and Mr. Red Horn Bull.” (from Elizabeth Hutchinson, ‘When the “Sioux Chief’s Party Calls”: Käsebier’s Indian Portraits and the Gendering of the Artist’s Studio’, American Art, Vol. 16, No. 2, Summer, 2002).

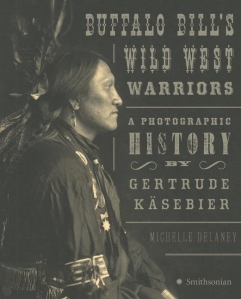

In over five years Käsebier produced around fifty portraits of Indian men, women, and children. These were unusual works for the time: simple compositions, with the sitters only a few feet in front of the camera, captured by relaxed focus of the exposures. The artist printed the negatives in platinum or gum bichromate, a process in which the paper absorbs the emulsion, creating a matte, textured surface. She frequently adjusted her photographs by reworking a negative or by re-photographing an altered print. She produced a wide selection of tonalities, a less manufactured effect. These works were not strictly “black and white”, but included a wide range of greys as well as subtle warm nuances of gold and brown. Although they were static postures, there was still a sense of movement within the pictures by the interplay between the sharp foreground focus and a glimpse at the artist’s sparse modern studio in the background. The facial expressions were masterfully rendered, conveying an emotional quality to the portraits.

In over five years Käsebier produced around fifty portraits of Indian men, women, and children. These were unusual works for the time: simple compositions, with the sitters only a few feet in front of the camera, captured by relaxed focus of the exposures. The artist printed the negatives in platinum or gum bichromate, a process in which the paper absorbs the emulsion, creating a matte, textured surface. She frequently adjusted her photographs by reworking a negative or by re-photographing an altered print. She produced a wide selection of tonalities, a less manufactured effect. These works were not strictly “black and white”, but included a wide range of greys as well as subtle warm nuances of gold and brown. Although they were static postures, there was still a sense of movement within the pictures by the interplay between the sharp foreground focus and a glimpse at the artist’s sparse modern studio in the background. The facial expressions were masterfully rendered, conveying an emotional quality to the portraits.

As Käsebier’s photographs of the Sioux were reproduced in women’s magazines like Harper’s Bazar and the Delineator, there was a sense that she directed them mainly at female readership. The Times noted that “Mrs. Käsebier and the young women artists who share the studio with her gaze at their guests with a feeling of deep artistic appreciation.” Elizabeth Hutchinson, author of The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890-1915 (Duke University Press, 2009) wrote in an insightful article how, “Käsebier’s interest in Native Americans was linked to women’s complex exploration of economic, sexual, artistic, and social empowerment at the turn of the last century. (…) It is important to see Käsebier as a woman artist working within contemporary standards of feminine behaviour. The appeal of the Indian portraits to women relates to exciting shifts taking place in these standards. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, women like Kasebier sought artistic training, opened studios, and submitted work to exhibitions in unprecedented numbers. Drawing on John Ruskin’s definition of art as a means of stimulating the intellect and spirituality of its viewers, women argued that artistic endevor was appropriate to their sphere, which included caring for the moral welfare of family and community. Such arguments legitimized women’s exploration of artistic careers, but also reinforced ideas of gender difference. As a result, women frequently entered fields of artistic endeavor that were less lucrative and less highly regarded. Influential critics and educators defined specific media-such as photography, illustration, and needlework-and also genre-particularly representations of children and women-as appropriate for women. (…) From the beginning of her career, Käsebier made portraits of “New Women”-women who were interested in developing a sense of individuality and power through work or other public (…) The Indian portraits reinforced this association with contemporary ideas about gender even as they helped to open a space for women artists in male-dominated artistic circles.” (Elizabeth Hutchinson, ‘When the “Sioux Chief’s Party Calls”: Käsebier’s Indian Portraits and the Gendering of the Artist’s Studio’, American Art, Vol. 16, No. 2, Summer, 2002). It seemed that the images of the Native Indians were close to the artist’s heart and removed from her rest of her artistic or commercial work, as she rarely exhibited or sold them.

As women became more empowered, it seemed that they may have looked upon these Indian portraits from an objectifying angle. Hutchinson wrote that “Some Indian Portraits” published in Everybody’s Magazine encouraged just such a reaction: “It describes the models’ bodies as desirable through images, text, and overall layout. For example, the article identifies the feathers in Amos Two Bulls’s headdress as signs that he is looking for a wife. (…) Sammy Lone Bear’s missives describe meeting “nice girls” in Philadelphia and sending his correspondent “sweet kisses.” The Indians’ interest in socializing with European-American women invites the female reader to feel free to socialize with them. (…)”Some Indian Portraits” plays with the familiar trope of the sexually charged relationship between artist and model.” The 19th century American ladies admiring the male beauty of the Sioux pictured in their magazines transcended gender rules, as well as racial prejudices. They were attracted to the obvious exoticism of the Indians’ attire replicated in the fashions of the department stores of their time. However, their appreciation might have also felt like a small act of rebellion in a society in which women’s place was predominantly in the kitchen or raising children, in which they had no spending money or careers of their own and in which they were expected to be devoted to meeting the needs of their spouses. The women’s reaction to the liberated Käsebier’s Indian portraits provided a glimpse at the feminist revolutions still to come.

As women became more empowered, it seemed that they may have looked upon these Indian portraits from an objectifying angle. Hutchinson wrote that “Some Indian Portraits” published in Everybody’s Magazine encouraged just such a reaction: “It describes the models’ bodies as desirable through images, text, and overall layout. For example, the article identifies the feathers in Amos Two Bulls’s headdress as signs that he is looking for a wife. (…) Sammy Lone Bear’s missives describe meeting “nice girls” in Philadelphia and sending his correspondent “sweet kisses.” The Indians’ interest in socializing with European-American women invites the female reader to feel free to socialize with them. (…)”Some Indian Portraits” plays with the familiar trope of the sexually charged relationship between artist and model.” The 19th century American ladies admiring the male beauty of the Sioux pictured in their magazines transcended gender rules, as well as racial prejudices. They were attracted to the obvious exoticism of the Indians’ attire replicated in the fashions of the department stores of their time. However, their appreciation might have also felt like a small act of rebellion in a society in which women’s place was predominantly in the kitchen or raising children, in which they had no spending money or careers of their own and in which they were expected to be devoted to meeting the needs of their spouses. The women’s reaction to the liberated Käsebier’s Indian portraits provided a glimpse at the feminist revolutions still to come.

Reblogged this on Buffalo Doug and commented:

Artlark provides a fascinating introduction to the American Indian photography of Gertrude Kasebier. Here’s the post:

LikeLike

Her work is truly remarkable. She continues to inspire new generations of photographers.

LikeLike

yes, what an example! thank you for reading 🙂

LikeLike

Love following your blog!!! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, we are thrilled you like it, Clanmother ♡

LikeLike

thank you both very much. we could only provide a glimpse at her work, hopefully enough to stir up more interest!

LikeLike

I’d never heard of her work. Looks very intriguing.

LikeLike

Great stuff. I just wrote a short, shallow post on Anne Brigman who sounds as if she was very likely to have crossed Ms. Kaserbier’s path as a contemporary female pictorialist and acquaintance of Alfred Steiglitz. Glad for the exposure to this remarkable photographer.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLike

Nice post…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on msamba.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Manolis.

LikeLike