May

17

May

17

Tags

Fashion, Mondrian Style

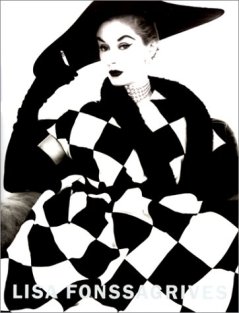

On the 17th of May 1911, the Swedish fashion model Lisa Fonssagrives, widely credited as the first ever supermodel, was born in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. A classic Scandinavian beauty “with impossibly high cheekbones and a cool, penetrating look of well-born entitlement” (Harold Koda, Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion), she posed for some of the most famous photographers of the age, including Horst P. Horst, George Hoyningen Huene and her second husband, Irving Penn, with whom she developed – according to Vogue publisher Alexander Liberman – “an extraordinary relationship between a photographer and a model.” Discovered in 1936 in a Parisian elevator by photographer Willy Maywald, her modelling career started right there and then. She had come to Paris to teach dance, but ended up as one of Vogue’s favourite models instead. However, she continuously compared modelling to dance, the latter being probably the secret of her impeccable posture and grace. She was the first ever fashion model to be honoured by a cover story in Life magazine, and in 1949 her face appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

On the 17th of May 1911, the Swedish fashion model Lisa Fonssagrives, widely credited as the first ever supermodel, was born in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. A classic Scandinavian beauty “with impossibly high cheekbones and a cool, penetrating look of well-born entitlement” (Harold Koda, Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion), she posed for some of the most famous photographers of the age, including Horst P. Horst, George Hoyningen Huene and her second husband, Irving Penn, with whom she developed – according to Vogue publisher Alexander Liberman – “an extraordinary relationship between a photographer and a model.” Discovered in 1936 in a Parisian elevator by photographer Willy Maywald, her modelling career started right there and then. She had come to Paris to teach dance, but ended up as one of Vogue’s favourite models instead. However, she continuously compared modelling to dance, the latter being probably the secret of her impeccable posture and grace. She was the first ever fashion model to be honoured by a cover story in Life magazine, and in 1949 her face appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

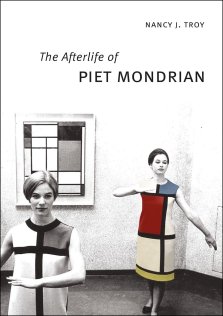

In 1944, Fonssagrives took part in a rather unusual photo shoot that took place in the New York apartment of artist Piet Mondrian, the father of non-figurative geometric abstraction and founder of Neoplasticism. Mondrian, who had died a month earlier, left behind his studio, a living and lived space which was hugely evocative of his paintings. “[H]e applied rectangles of coloured cardboard to many of the wall surfaces and to some of the tables, cabinets, and storage shelves he made for himself from wooden crates that he  painted white. “ (Karen Painter, Thomas E. Crow, Late Thoughts: Reflections on Artists and Composers at Work). “The spaces in which Mondrian lived and worked functioned like three-dimensional sketches for the paintings, although they are best understood as sites of compositional experimentation rather than designs directly linked to individual paintings. Mondrian’s surroundings enabled the artist to visualize the utopian future he imagined, when art would cease to be separate from life itself: “Of course art then will become less ‘Art’; but is not ‘Art’ a heritage of the past for us?” he asked in one of the late commentaries he left behind when he died.” (Painter, Crow)

painted white. “ (Karen Painter, Thomas E. Crow, Late Thoughts: Reflections on Artists and Composers at Work). “The spaces in which Mondrian lived and worked functioned like three-dimensional sketches for the paintings, although they are best understood as sites of compositional experimentation rather than designs directly linked to individual paintings. Mondrian’s surroundings enabled the artist to visualize the utopian future he imagined, when art would cease to be separate from life itself: “Of course art then will become less ‘Art’; but is not ‘Art’ a heritage of the past for us?” he asked in one of the late commentaries he left behind when he died.” (Painter, Crow)

After Mondrian’s death, his sponsor as well as heir and executioner of his estate, Harry Holtzman, kept the apartment intact for several months, showing off the space in which the artist had lived and worked to anyone interested. Recognizing the importance and artistic value of Mondrian’s environment, he allowed photographic and filmic documentation of the studio before letting it go. One of these photographic sessions featured the famous supermodel Lisa Fonssagrives. The model posed to her then husband Fernand Fonssagrives wearing black dresses designed by leading American fashion designers. “In these images, Mondrian’s paintings and his studio seem to have lost the stable, singular identity that the recently deceased artist had been able to assure them. No longer confined to the realm of high art, where they functioned as expressions of Mondrian’s utopian thoughts about painting and architecture, they took on an additional dimension as a banal and decorative backdrop for the display of women’s clothes.” (Painter, Crow).

Published in Town and Country magazine in June 1944, the pictures “established a precedent for subsequent exploitation of Mondrian’s work in the world of fashion, where for example, a painting by Mondrian was used to adumbrate the “uncluttered look” that Vogue promoted in its issue of 1 January 1945. More surprising, perhaps, was the juxtaposition of fashionable clothing with Mondrian’s work not in a women’s magazine but in the pages of ARTnews, where the painter’s uncompromisingly abstract, neoplastic style slipped back and forth between the apparently converging poles of high art and popular culture. …The collapse of the distinction between high art and female fashion was nothing new, nor was it unique to Mondrian in the mid-1940s; what is striking is the swiftness with which his strictly abstract, modernist work was assimilated to fashion and popular culture, even as it was being shown extensively in major museum retrospectives organized shortly after his death.” (Painter, Crow). The longevity of the eye-catching ‘Mondrian look’ can be clearly witnessed in today’s fashion too: the so-called ‘colour blocking’ trend revived in 2009 still inspires clear-cut lines delineating areas of fresh vibrant pigment in textiles designed by Marc Jacobs, Ben de Lisi, Jasper Conran, Julien Macdonald, Hugo Boss and many others.

Published in Town and Country magazine in June 1944, the pictures “established a precedent for subsequent exploitation of Mondrian’s work in the world of fashion, where for example, a painting by Mondrian was used to adumbrate the “uncluttered look” that Vogue promoted in its issue of 1 January 1945. More surprising, perhaps, was the juxtaposition of fashionable clothing with Mondrian’s work not in a women’s magazine but in the pages of ARTnews, where the painter’s uncompromisingly abstract, neoplastic style slipped back and forth between the apparently converging poles of high art and popular culture. …The collapse of the distinction between high art and female fashion was nothing new, nor was it unique to Mondrian in the mid-1940s; what is striking is the swiftness with which his strictly abstract, modernist work was assimilated to fashion and popular culture, even as it was being shown extensively in major museum retrospectives organized shortly after his death.” (Painter, Crow). The longevity of the eye-catching ‘Mondrian look’ can be clearly witnessed in today’s fashion too: the so-called ‘colour blocking’ trend revived in 2009 still inspires clear-cut lines delineating areas of fresh vibrant pigment in textiles designed by Marc Jacobs, Ben de Lisi, Jasper Conran, Julien Macdonald, Hugo Boss and many others.

I wonder what would “Walter Benjamin” would have to say on this subject, this is a footnote to your article 🙂

LikeLike

very good link, many thanks ))

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing 🙂

LikeLike

thanks for reading !!

LikeLike

How elegant!

Thanks for following my posts. If only I was as elegant as my gravatar or Lisa Fonssagrives. One tries…!

LikeLike

Always interesting! I like how you combined introducing the striking Lisa Fonssagrives with the information about Mondrian’s apartment and art. Mondrian’s influence on modern design does indeed seem to be widespread.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very nice. I love Mondrian style! I do research in physics and work with cellular automata. I’ve made a automaton to study glassy systems. I obtained through simulations a pattern for a vitreous system which (at least for me and my colaborators …..) looks like a Mondrian painting. Please, see the post at my blog: http://taniabrazil.com/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always a thrill to have Mondrian centre stage.

Have recently had much interest in this style of Interior & furniture. B

LikeLike

love how much information is in this article. great can’t wait till your next post!

LikeLike