July

26

July

26

George Grosz: War→Madness→Dada

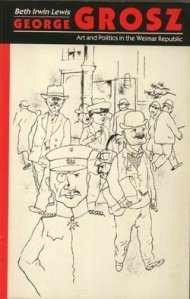

On the 26th of July 1893, German artist George Grosz was born in Berlin. From an early age, Grosz had passionate ideological views. In January 1919, he was arrested during the Spartakus uprising in Berlin, a general strike accompanied by armed battles, which was being suppressed by the Weimar government, marking the end of the German revolution. Grosz escaped arrest using fake identification and he soon joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). In 1921, the artist was accused of insulting the army, which resulted in a 300 German Mark fine and the destruction of a collection of his work entitled Gott mit uns (“God with us”), a satire on German society. Grosz left the KPD in 1922 after having spent five months in Russia and meeting Lenin and Trotsky, because of his antagonism to any form of dictatorial authority. Bitterly anti-Nazi, Grosz left Germany for the USA in 1933 shortly before Hitler came to power but returned to Berlin a few years before his death (caused by a drunken stumble down a flight of stairs). Today, Grosz, a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Objectivity group, is mostly remembered for his off the wall drawings and oils of Berlin life from the 1920s. One of his better known works from this period (see feature image) is Eclipse of the Sun.(1926) “It represents a scathing critique of the military industrial complex that controlled Weimar Germany where power and greed reigned supreme. Bureaucrats, who are literally “mindless,” attend to the corrupt dealings of the corpulent industrialist and the President of the Reich, Paul von Hindenburg. The sun, a symbol of life, is eclipsed by a dollar sign, a symbol of greed. The donkey, representing the German burgher, has blinders on to signify his ignorance. A small child, representing youth or perhaps a dissident voice, is kept imprisoned below, demonstrating the lack of concern for future generations. The convoluted perspective of the image underscores the instability of Weimar Germany.” (Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, N.Y.)

On the 26th of July 1893, German artist George Grosz was born in Berlin. From an early age, Grosz had passionate ideological views. In January 1919, he was arrested during the Spartakus uprising in Berlin, a general strike accompanied by armed battles, which was being suppressed by the Weimar government, marking the end of the German revolution. Grosz escaped arrest using fake identification and he soon joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). In 1921, the artist was accused of insulting the army, which resulted in a 300 German Mark fine and the destruction of a collection of his work entitled Gott mit uns (“God with us”), a satire on German society. Grosz left the KPD in 1922 after having spent five months in Russia and meeting Lenin and Trotsky, because of his antagonism to any form of dictatorial authority. Bitterly anti-Nazi, Grosz left Germany for the USA in 1933 shortly before Hitler came to power but returned to Berlin a few years before his death (caused by a drunken stumble down a flight of stairs). Today, Grosz, a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Objectivity group, is mostly remembered for his off the wall drawings and oils of Berlin life from the 1920s. One of his better known works from this period (see feature image) is Eclipse of the Sun.(1926) “It represents a scathing critique of the military industrial complex that controlled Weimar Germany where power and greed reigned supreme. Bureaucrats, who are literally “mindless,” attend to the corrupt dealings of the corpulent industrialist and the President of the Reich, Paul von Hindenburg. The sun, a symbol of life, is eclipsed by a dollar sign, a symbol of greed. The donkey, representing the German burgher, has blinders on to signify his ignorance. A small child, representing youth or perhaps a dissident voice, is kept imprisoned below, demonstrating the lack of concern for future generations. The convoluted perspective of the image underscores the instability of Weimar Germany.” (Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, N.Y.)

There has been a significant amount of writing about the Dadaists, particularly, George Grosz, his life and art, in relation to psychiatry. Amongst many of these artists, he experienced or simulated mental illness during WWI. The Dada ‘state of mind’ as well as their artistic output has since been connected to mental health conditions such as paranoia or neurasthenia, often resulting from post-traumatic stress following the violence and atrocities of life in wartime as well as on the front. Michael White, author of Generation Dada (2013, Yale University Press) writes that, “there is a substantial body of literature on Grosz that has examined his depiction of sexual violence and murder in the period and  located it centrally to an understanding of his work. The common strand to these approaches is to perceive the simulation of trauma in Dada montage or the depiction of sexual violence as attempts to shore up a threatened or damaged masculinity. By analogising Dada montage to the psychiatric procedures of shock treatment, Brigid Doherty specifically casts it as reparative in intent and devised for an audience that was itself ‘traumatophile’, in search of relief from anxiety through shock.” (Michael White, ‘The Grosz case: Paranoia, Self-Criticism and Anti-Semitism’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2007).

located it centrally to an understanding of his work. The common strand to these approaches is to perceive the simulation of trauma in Dada montage or the depiction of sexual violence as attempts to shore up a threatened or damaged masculinity. By analogising Dada montage to the psychiatric procedures of shock treatment, Brigid Doherty specifically casts it as reparative in intent and devised for an audience that was itself ‘traumatophile’, in search of relief from anxiety through shock.” (Michael White, ‘The Grosz case: Paranoia, Self-Criticism and Anti-Semitism’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2007).

“The Dadaists were the inventors of the metaphor of madness as a form of war resistance. For instance, Jean Arp, who was discharged from military duty on the grounds of mental illness (which he simulated), wound up in Switzerland where he met the founders of what soon enough would be called Dada. One way of posing the question of origins is the following: when did faking madness start, and when did opposition to the war begin to take the form of simulating insanity? Jean Arp said, ‘We were looking for an elementary art which would be capable of saving humanity from the furious insanity of the times. We aspired to a new order which could restore the equilibrium between heaven and hell.’ Equally, Tristan Tzara was adamant that, ‘Each man must cry: there is a great destructive, negative job to do: sweep away, clean up.’ (from Annette Becker, ‘The Avant-Garde, Madness and the Great War’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 1, Special Issue: Shell-Shock, Jan., 2000). The overwhelming Dadaist message was: out with the old, in with the new!

In Berlin, Grosz and John Heartfield organized the first International Dada Fair in 1920. Otto contributed with his canvas entitled War Cripples: A Self-Portrait (1920) which portrayed four war invalids with severely broken bodies and spirits. Many Dada artists and writers actually ended up committing suicide, it somehow was their ultimate stand against war and what was left in its aftermath… Anette Becker wrote of the Dadaist artist: “The war is over; he is still in uniform, and he spins his metaphors like a cinema reel.” From their part, the incoming Nazis wanted to destroy the resulting ‘crude’ or ‘degenerate’ art. In the 1937 catalogue of the censored ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition, there is a direct quotation from Hitler, who in 1934 said: ‘Those who look for novelty above all can only go mad’. “Modern art, and in particular German  expressionism, contradicted root and branch all the aesthetic and social values of Nazism. In Dix, or Grosz or Beckmann, where is respectability, order, security? Their work is a cry of despair of men trapped in a personal and collective drama, one in which the war had played a decisive part. With the exhibition, and with the destruction of a number of works from it, the nazis wanted to prove the moral decadence, the degeneracy of Weimar. Of all their enemies, the nazis chose Otto Dix and George Grosz as exem-plary degenerates in the exhibition. Is it surprising that this was so, given the importance of the war in their art, the place of the disabled and the disfigured, who constituted a veritable ‘imagery of military sabotage’?” (Annette Becker).

expressionism, contradicted root and branch all the aesthetic and social values of Nazism. In Dix, or Grosz or Beckmann, where is respectability, order, security? Their work is a cry of despair of men trapped in a personal and collective drama, one in which the war had played a decisive part. With the exhibition, and with the destruction of a number of works from it, the nazis wanted to prove the moral decadence, the degeneracy of Weimar. Of all their enemies, the nazis chose Otto Dix and George Grosz as exem-plary degenerates in the exhibition. Is it surprising that this was so, given the importance of the war in their art, the place of the disabled and the disfigured, who constituted a veritable ‘imagery of military sabotage’?” (Annette Becker).

Feature Image: George Grosz (1893-1959), Eclipse of the Sun, 1926, Oil on canvas, 81-5/8 x 71-7/8 in, Heckscher Museum of Art, N.Y.

Great post! Related to it, George Grosz works are included in the World War I and the Visual Arts exhibition at the Met in NYC which is opening on July 31, 2017. It will be an opportunity to revisit Grosz’s works among his contemporaries.

Tatyana at http://www.arts-ny.com

LikeLike